Picture this: a child is learning how to play with an exciting new toy with lots of possible actions to perform (think Bop It). They’re playing with two adults, who each teach them how to perform a different action on the toy. Later, when the child is playing alone with the toy, someone new comes in who’s never seen this toy before. They ask the child to teach them how to play with the toy. How does the child choose which action to teach to them?

We know a lot about how children learn – which processes they rely on and which cues they pay attention to – but we know a lot less about children as teachers and what contributes to a child’s choice of what to teach. Children pay attention to different aspects of their environment that could all affect what they choose to teach to someone else. This includes anything from inherent properties of information to be taught (is the action on the toy easy, fun, rewarding?) to features of the person who taught it to them (was the person familiar, confident, friendly?).

One of these features is action complexity: how difficult something is to do. It makes sense that in general, children would rather teach something that they were confident they could do correctly themselves, or that doesn’t take them too much effort to teach. Although this intuitively makes sense, this hasn’t been studied before.

Another of these features is the pedagogical nature of teaching: whether or not there were explicit cues that signal to children that they are being taught. Although children learn both through imitating what they’ve observed and explicit teaching, it could be the case that if they have been taught something explicitly, they will be more likely to share it with others. In fact, that’s exactly what was found previously1. The authors suggested that this was because two-year-old children interpret something that was explicitly taught to them as important (or “culturally relevant” for knowledge transmission in human society), and therefore should be passed on to other members of their community. However, it could also be that infants aren’t thinking that hard about it – it’s just that the features of explicit teaching in the study by the authors (e.g. direct eye contact and the cutesy voice we put on when we talk to young children – “parentese”2) somehow highlighted the action by making it more salient (i.e., prominent), and therefore it was more likely to be taught to someone later.

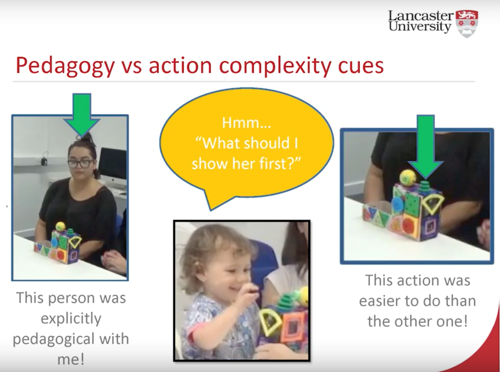

In order to help figure out which of these interpretations was true, we designed an experiment where we pitted two competing action features against each other. Upon inviting children and their primary caregivers to the Lancaster University Babylab, we had two unfamiliar adults teach 2-year-olds actions on toys we’d designed ourselves. One of these actions was very easy to do but wasn’t explicitly taught to the child, instead just being stumbled upon accidentally by the adult. The other action was more difficult to do, but was explicitly taught to the child, using all the features that highlight to the child that they are being taught something (direct eye contact, parentese, and being told “this is how you do it”). We wanted to know which of these actions the child would then choose to teach to a new adult who had (allegedly) never seen the toy before.

If children understand that the action that was taught to them was “culturally relevant”, and therefore something that should be passed on to other members of their group, then they should have a preference for teaching to the new adult the more difficult action that was explicitly taught to them. Otherwise, they may have no preference, or a preference for teaching the easier action because they’re more confident with it themselves!

We found that children most often taught both actions to the new adult, but they had a strong preference in favour of teaching the easy action to the new adult. So, it was likely that it wasn’t that the child thought that everything that was explicitly taught to them was culturally relevant and therefore worth passing on to someone new, but instead that the child was just influenced by how easy the action was. However, we still didn’t know whether this was because both of these features (easiness and explicit teaching) had been fighting against each other and easiness had won, or whether maybe the explicit teaching had no effect at all.

In order to figure this out, we ran another version of the experiment but where actions were matched for how easy they were, and the only thing that was different was the way the actions were taught – i.e. we ran a replication of the original study that we had based ours on. Replication studies are very important, because there are many reasons why results that have been found in the past will not be found again, and a result can only be relied upon once it has been shown multiple times3.

When we ran this version of the study, we found that the children had no preference for which action to teach to the new adult! Even though one action had been taught to them explicitly and the other had only been stumbled upon accidentally, children didn’t seem to take this into account when teaching the actions to an adult who had never seen the toy before.

Overall, two-year-olds are quite keen to teach adults what they know! In our study, we found support for the fact that the complexity of the information being taught to children affects their eagerness to teach it to someone else. However, we didn’t find that the manner it’s taught in had any effect. This is good news for all the busy parents out there trying their best to homeschool their children at the moment – they’re learning all the time even when you don’t have time to sit down and properly teach them something, and they might even teach you a thing or two themselves!

This work forms part of both Marina Bazhydai & Priya Silverstein’s doctoral research and has been published in the Developmental Science4 journal.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to all the caregivers and children who took part – we couldn’t do it without you! M. Bazhydai and P. Silverstein were funded by Leverhulme Trust Doctoral Scholarships [DS-2014-014]. This work was supported by the International Centre for Language and Communication Development (LuCiD) at Lancaster University and University of Manchester, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (UK) [ES/L008955/2].

Further information: For example videos and data, please see here: https://osf.io/e2hvj/.

References:

- Vredenburgh, C., Kushnir, T., & Casasola, M. (2015). Pedagogical cues encourage toddlers’ transmission of recently demonstrated functions to unfamiliar adults. Developmental Science, 18(4), 645–654.

- Csibra, G., & Gergely, G. (2009). Natural pedagogy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(4), 148 153.

- Meyer, M. N., & Chabris, C. (2014). Why Psychologists’ Food Fight Matters. Slate. https://slate.com/technology/2014/07/replication-controversy-in-psychology-bullying-file-drawer-effect-blog-posts-repligate.html

- Bazhydai, M., Silverstein, P., Parise, E., & Westermann, G. (2020). Two-year-old children preferentially transmit simple actions but not pedagogically demonstrated actions. Developmental Science, e12941.